A Conversation with General Thomas V. Draude

My infatuation with the subject of this interview, General Thomas Draude, is explained by my very being in Florida. I am a Philosophy, Politics and Economics undergraduate at the University of Exeter and for a year I lived and studied in the wildly contrasting city of Tampa, Florida.

Being a Londoner, the big city life didn’t faze me, but the culture shock did. I had never been to America, so this was a baptism of fire of sorts.

In my first semester at the University of South Florida, I took a class on the Vietnam War with General Draude and instantly appreciated his anecdotes and impressive class speakers. A Vietnam class taught by a Vietnam Veteran – this was the exact kind of thing I had come to Florida for, I thought. Over the next couple of months, I grew fond of the sharply dressing, quick witted, wise old General.

When I heard the General was taking another class in semester two, this time on Why and How we Fight U.S. Wars, I jumped at the opportunity. It was after one of these classes that this interview was conducted.

Over the course of the interview we discuss his upbringing, his journey in the Marines, his time in Vietnam, his role as Head of Deception Operations in Desert Storm, his takes on the War of Terror and his advice for the youth, government and military of America.

The following piece is my attempt at condensing our almost two-hour long interview into an enjoyable read. The whole interview in the General’s words can be found at the top of this page for listening at your own pace.

The article will conclude with three parting messages from General Draude. For the youth, the government and the military of today.

The Early Years

General Thomas Draude was born in 1940 in Kankakee, Illinois. His father was a first-generation German immigrant and his mother was the daughter of Irish immigrants. General Draude recalls his childhood with affection, calling it a ‘golden opportunity, a blessing.’

His adoration for the military began young with the onset of U.S. involvement in World War Two.

‘I was perhaps four years old, but I remember it as if it was yesterday. I remember my father had a friend who decided to join the Marine Corps after Pearl Harbour.

‘My father said this man is a Marine and this is the best there is. From that point on I wanted to be a Marine.’

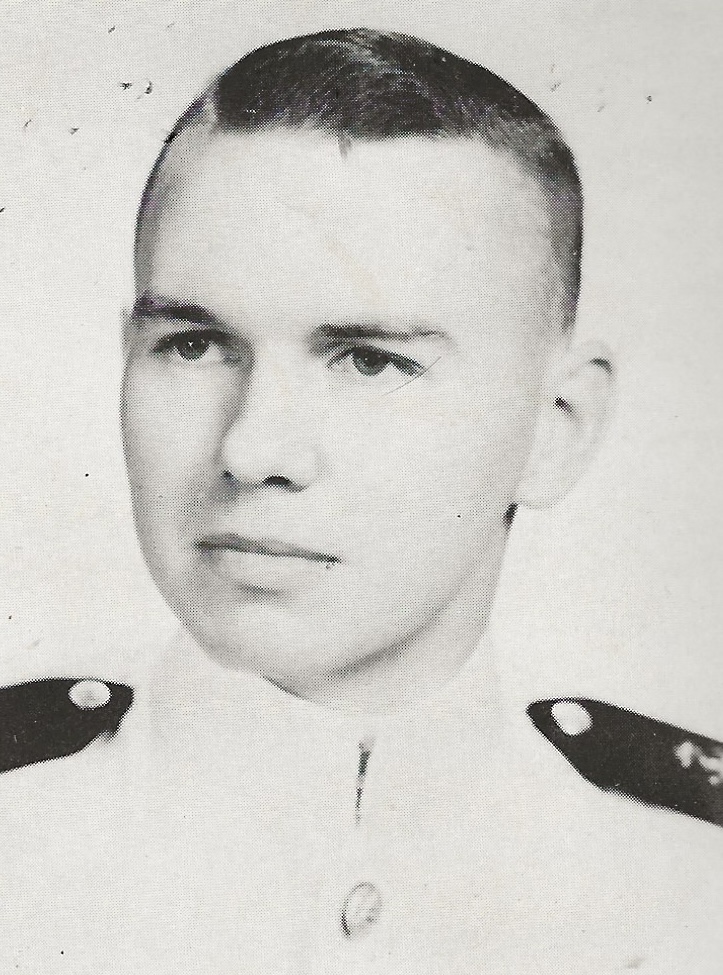

The General went on to perform well at school, graduating from St. Patrick Central High School as a Valedictorian and joined the Naval Academy in Annapolis in June 1958, aged eighteen.

I was surprised when the General confessed that at this point in his life, he was ‘a self-conscious fat kid.’

This was in stark contrast to the man I had got to know, who was confident, witty and well-presented. He never wore the same jacket twice and had a Naval Academy class ring collection to rival any other. At no point did it occur to me that at one point, like the rest of us, he was uncomfortable in his own skin.

‘Sometimes I doubted whether I could hack it. I suffered from an inferiority complex, but it drove me to be the best version of myself.’

General Draude graduated from both the U.S. Naval Academy and The Basic School with honours, and in 1963 commanded an infantry platoon destined for Okinawa. Here, early in his career, he faced adversity and discrimination.

‘My first company commander looks over my record and says, “I might as well tell you from the beginning that there are two types of people in this world that I hate. Naval Academy graduates and Catholics.”

‘Being both of those things made for an interesting dynamic, but we managed to work past it. I remember thinking being a Naval Academy graduate might not be the great advantage I had once thought!’

Vietnam

In March of 1964, General Draude’s story takes a dramatic turn, he is shipped to Vietnam for the first time with his platoon. This is where, only a year later, the young Marine would face life, death and tragedy head on.

At this point, before the Gulf of Tonkin incident of August 1964, the U.S. commanded an advisory and security role in Vietnam. Draude and his platoon provided security for the U.S. Marine aviation unit, near and on parts of Da Nang airfield.

After the Gulf of Tonkin incident however, U.S. involvement in Vietnam changed drastically. The U.S. transitioned from occupying an advisory role to an active combatant role. For the second time since World War Two, America was at war.

‘We were part of Operation Starlite in August of 1965. It was the first major multiple battalion U.S. engagement in Vietnam.

‘At the time I had been selected to be the Battalion Adjutant. I wanted to be Executive Officer or Platoon Commander with my Marines, but you have to have someone doing the paperwork. I was stuck in the rear with the gear.

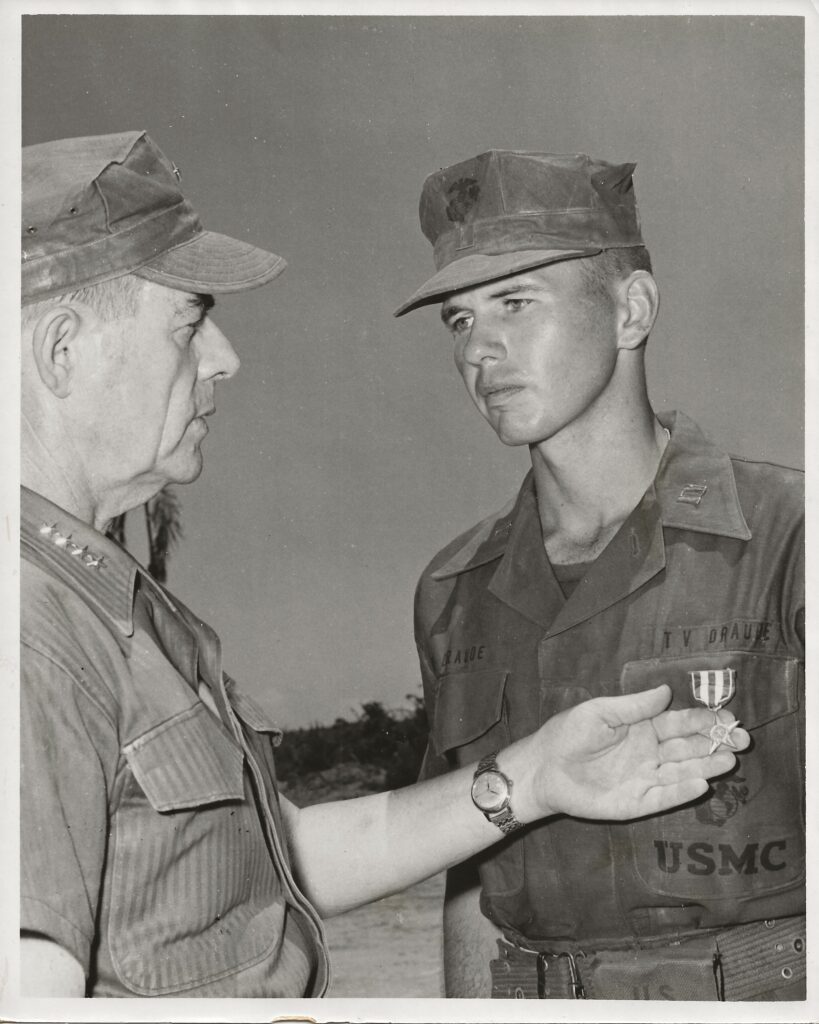

‘I kept trying to work back into the real Marine Corps [Rifle Companies] and eventually I did as Executive Officer. My company commander got wounded so I took over as First Lieutenant.’

Although most would wince at this sudden summoning into combat, General Draude admitted that he ‘was actually looking forward to it.’

He continued to say, ‘it was an opportunity to prove myself and be a good officer. I’m ashamed to say it but this is what I had trained for and this is what Marines are supposed to do.’

Soon, however, the gruesome realities of war were staring at the young officer down the barrel of a Vietcong Kalashnikov.

‘I didn’t know any better then…’

Q: What was the scariest moment in Vietnam for you?

‘The scariest moment was when we got hit by a Vietcong Battalion in 1966. We were well outnumbered but fortunately in defensive positions.

‘Nevertheless, waking up to the sound of Vietcong tracer rounds going over your head sure took your mind off sex!’

Q: And your proudest?

‘My proudest moment was when I was almost relieved of my command.

‘We had to take a Hamlet, which we didn’t realise was reinforced by a Vietcong battalion. I brought in all the support arms I could…but it wouldn’t budge.

‘Nightfall was coming fast, and you don’t want to attack at night because the enemy can tell where you are, but you can’t tell where they are. So, I gave the order for fix bayonets.’

‘There was calm resolve among the Marines, they knew that this was as grizzly as it was ever going to get. In a little bit of time, we were going to slash or bash another human being to death. At either end of my rifle would be a dead person.‘

‘We made the attack and it was successful. But I learned that one of my squad leaders, Corporal Frederick Miller from Berlin, Ohio had been killed and was outside of the lines. I told my Marines to take me to where he was.

‘I put him on my back and brought him back within our lines. The next day the Battalion Commander comes in and sees the blood all over my flak jacket and asks if I had been wounded. I said no and explained the situation. He was really upset and made me promise to never do something like that again [cross the lines].

‘This was one of those life changing moments. If I remain silent, I choose to live with that for the rest of my life. I told him that if it happened again, I’d do the same thing, because I will never leave behind a dead or wounded Marine.

‘Now he’s going ballistic and is in the process of relieving me of my command. All of my boyhood dreams of being a Marine were gone. I was finished in the Marine Corps – you don’t survive being relieved in combat! And to add to it, you have a Brigadier General jumping off a helicopter to grab what’s left of my fanny – ironically the position I would later go on to hold in Desert Storm, Assistant Commander of the First Marine Division.

‘He comes in, grabs me by the hand and starts pounding me on the back. He turns to the Battalion Commander who is relieving me, and says “Colonel, with company commanders like this, how can you go wrong?”, and walks away. It was that close!

‘It was my proudest moment because of the physical courage of the attack, but also because of the moral courage it took to tell the Battalion Commander what he didn’t want to hear.’

Q: Did you ever feel like the U.S. was doing the wrong thing in Vietnam?

‘The Vietnamese were caught in the crossfire so many times, so much suffering. So many innocents died, that still plagues me. But when we had a chance, we just had to do the right thing.

‘I remember one little girl had Clubfoot; she was literally walking on the outside of her ankles. We worked with the Vietnamese to get her to one of our surgeons who corrected it. I didn’t have any children at that point, but I really got a sense of what it was like to make a child’s life better.’

When asked whether the U.S. was doing the right thing in Vietnam, The General responded, ‘we showed that we were willing to put literal skin in the game to hold it there [the global expansion of Communism].’

But admitted that ‘it didn’t seem we were fighting the right war. We said it was counterinsurgency, but it was really a war of attrition. It bothered me.

‘We could not kill our way out of the war, it was a bankrupt strategy. I got in trouble while teaching at Fort Bragg for saying that we were killing too many [Vietcong] rather than bringing them to our side. There had to be a better way!’

After Vietnam

General Draude was last in combat in Vietnam in 1970 when ‘the war was going pretty well from a U.S. standpoint.’

‘My last tour in Vietnam was with the Vietnamese Marines. Toughest guys I’ve seen. A real brotherhood was created. We lived, slept and ate with them side by side.

‘Some had tattooed on their arms “Sat Kong’” which meant “Kill Vietcong.” If they were captured, they surely would die, so it made them fight a little harder.

‘It hurt to see 1975, because I knew life was not going to be good for those left behind.

‘Some of them did eventually get out and came to D.C. and California as the two main points. I got to see some of them later. It was a thrill to see those who had survived.’

The General has been to Vietnam twice since the war.

‘It’s amazing, the greatest capitalists I have ever seen! Superhighways and high rises. I call it Communist Lite. Sort of like how Yugoslavia was at one time.’

Q: Did the U.S. lose in Vietnam?

‘I used to get angry at Senior Officers who said that we didn’t lose in Vietnam. If we didn’t lose, that exodus off the roof of the American embassy is the strangest victory parade I’ve ever seen!

‘It bothers me, the tendency the United States has developed of making promises and then reneging on them. Our word used to mean something, and I hope we get back to that point.’

General Thomas Draude

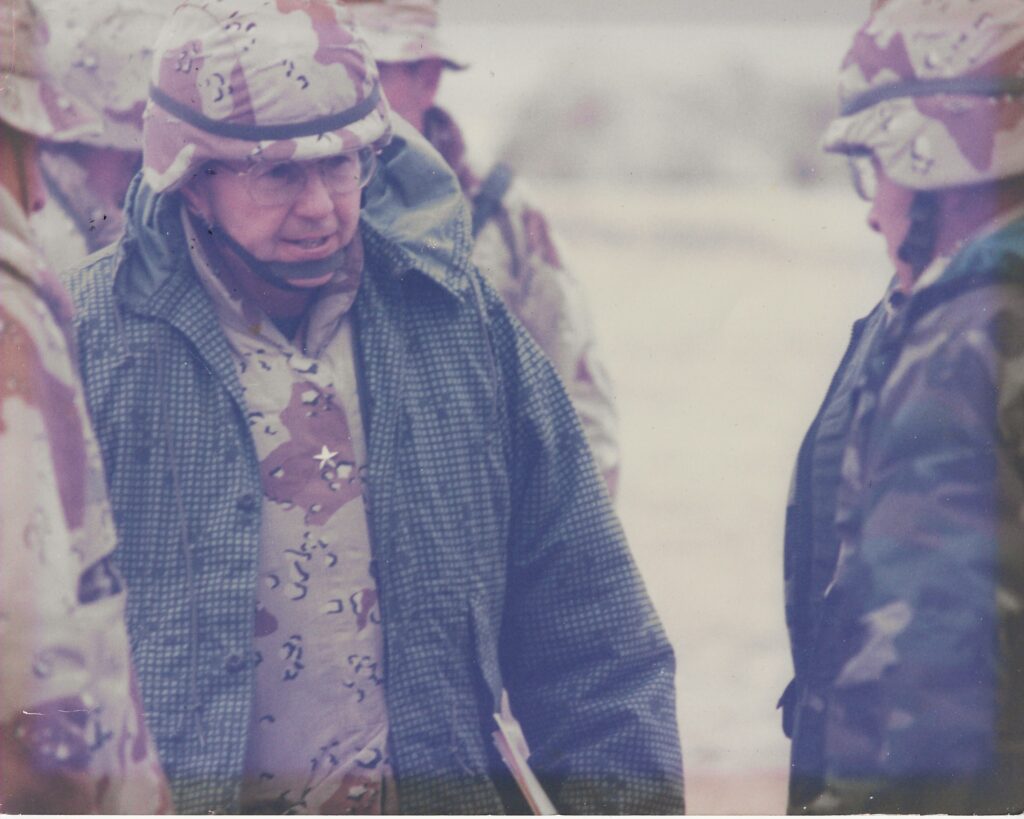

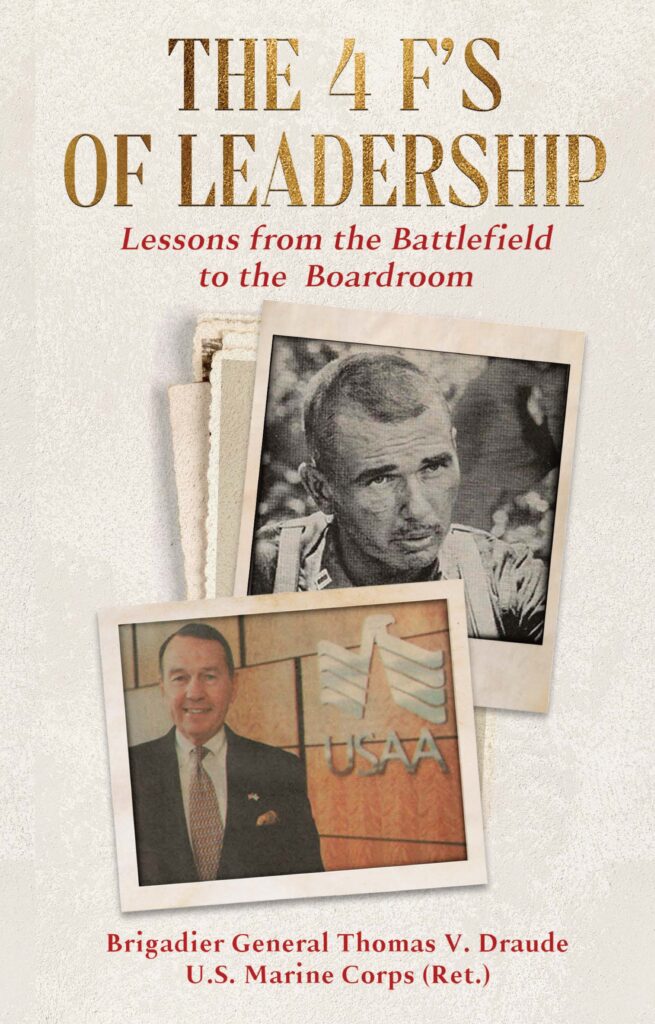

Draude was made a Brigadier General in 1989 during the H.W. Bush Presidency. This was the rank that he would go on to hold until his retirement from the Marine Corps in 1993.

Q: Was it always your aim to become a General?

‘The General stuff was never really on my mind. I just wanted to be the best Marine I could be. My wife was surprised when I made Major!’

The role, however, was not without its perks.

‘The best thing about being a General is that you can get things done. People have a tendency to listen to Generals.’

Shortly after being promoted to Brigadier General, Draude was assigned to the Pentagon to implement American magnate David Packard’s (of Hewlett-Packard) Defensive Management Report. The report, commissioned by the Department of Defence, outlined strategies for reducing costs.

‘On my first day as a general officer, I’m at the Pentagon heading this thing nobody knew anything about.

‘It was about saving money, so it meant going to the Department of Defence departments and saying we’re going to take some money back from you. Not a pleasant thought…’

Despite this uphill battle, Draude managed to have success in his year in the role, ‘we saved billions of dollars; it was amazing!’

Q: When did you find out you would be involved in Desert Storm?

‘I was in that job when the Iraqis invaded Kuwait in August of 1990. I thought another war, I’m pretty much done here, and I’ve got a lot of combat experience. Maybe I can make a difference.

‘I wrote a letter to our Commandant, General Gray, and asked to be used where he needed me. I believed it was the right thing to do.’

This decision, however, did take a toll on Draude’s family who were concerned about the safety of the then 50-year-old General.

‘The toughest part was going home and telling my wife I had volunteered for combat again. We had a 17-year-old spirited lad who was making life interesting for us.’

Despite family complications, General Draude believed the Gulf War was the perfect opportunity to make up for the mistakes his country had made in Vietnam.

‘I thought God, this is our reward for going through…all that stuff. You’ve got to learn from your mistakes.’

During the Gulf War, Draude served as the Head of Deception Operations.

The Amphibious Assault

As Head of Deception Operations, General Draude capitalised on the widespread media coverage of U.S. Marine Corps rehearsals that were conducted off the coast of Kuwait. They showed the 5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade training for what seemed like an amphibious assault on Kuwait City. One of the people convinced of an imminent amphibious assault was Saddam Hussein. He positioned between five and seven divisions on the coast facing the Gulf.

This resulted in Hussein’s men being ill prepared for coalition rear attacks formed of predominantly U.S., U.K., French and Saudi Forces through the deserts of Saudi Arabia. Coalition forces overwhelmed the Iraqi Army from behind and Kuwait was liberated in just four days.

‘He wanted to believe that we were going to do an amphibious assault. We never had to fight them, just circle behind them and hands up.’

Q: How do you think the war would have gone if the Amphibious Assault was actually orchestrated?

‘Much worse.

‘Those mines [in the bay of Kuwait City] had not been neutralised. There was no way we were going to get in there without casualties.

‘Even if we got in there, there was no beach. Here’s the city! Where are you going to go? It would have been a horrible disaster.’

‘In Vietnam, it was don’t think too much, kill the enemy. Here we fought with common sense.’

Commission on Women in the Armed Forces

In the wake of the success of the Gulf War, General Draude was selected in 1991 by President G.H.W. Bush to be a part of the Commission on Women in the Armed Forces.

This commission was formed to assess the roles of women in the U.S. military, and if, or how they should be expanded.

For the General, the Commission was ‘prompted by Desert Storm where women performed well, and the public started to ask, what’s going on?’

The committee was comprised of serving and retired Veterans, activists, historians and a sociologist.

‘Fifteen of us, most had an agenda, it was either women had gone too far, or women had not gone far enough.

‘I went in truly with a blank slate. No going in position so to speak.’

The General’s fatherhood however, played a crucial role in his decision-making process during the Commission.

‘I had seen my fair share of the grisliness and horror of combat and I didn’t want my daughter or anybody else’s daughter to go through that.

‘On the other hand, Loree [General Draude’s Daughter] was doing some amazing things down at Flight School in Pensacola.’

Loree Draude went on to be one of the first women in the U.S. Navy to deploy as a carrier-based jet pilot and was the first woman air-wing qualified Landing Signal Officer in combat jet squadrons, which broke significant barriers for women in the military.

Inspired by Loree’s strength and determination, General Draude became resolute in challenging the widespread bigotry that permeated the U.S. Military at the time.

Here, the General recalls a conversation that particularly irked him.

‘The Marine aviator general came in and said “there’s one thing you’ve got to understand, women cannot fly high performance aircraft. The G Force will put their uteruses right out.” I responded my daughter was down at Pensacola and I hoped to be a grandfather some day!’

Draude also believed that fitness tests were being given too much weight and were hindering the expansion of roles for women in the military.

‘The question of upper body strength kept coming up.

‘I served three times in Vietnam, I never once had to do a pullup.

‘You have to be fit and capable of doing the job regardless of age and gender, but do you have to run 3 miles in under 18 minutes to be a computer technician?

‘If I tried to max an 18-year old’s PFT [Physical Fitness Test] I’d die of a heart attack.

‘To sit here and say “you can’t” just because of the way you were created. That’s just not American.

‘We were not making use of the talents and abilities of over 50% of our population. It didn’t make any sense.

‘The only thing I voted against was women in ground combat units due to the living conditions. I may be wrong, but that’s just an old guy’s view on it.’

General Draude later expanded on this position in a lecture, in which he expressed his concern that women prisoners of war are much more likely to experience sexual assault than their male counterparts. However, women aviators were aware of this risk and did not shy away from serving their country.

Influenced by the Commission, the Clinton Administration lifted restrictions in 1993 on women serving in combat aviation roles and on combat ships. This marked a historical shift in policy regarding the role of women in the Armed Forces.

Q: What changes could be made today to further the role of women in the military?

‘I think we are moving in the right direction in knocking away the obstacles that preclude women. The retention rate in the Marine Corps is actually higher for women than men.

‘Part of the problem is sexual assault and harassment. The military has done horribly in that regard. We kept telling Congress we’ve got it under control, we didn’t.’

Q: And what changes can be made to make the military a more appealing option in general?

‘To make it more attractive in general, you’ve got to make it appealing for a youngster to serve.

‘That’s tough these days. So, I’ll tell you my radical plan.’

‘My idea is that every American citizen at age eighteen signs up to spend two years doing something for somebody else. It can be wearing the cloth of the military, but it doesn’t have to be. It can be in a nursing home, some place away from home. Where you learn to work and live with people who are different from you. That was the beauty of the services.’

There are clear parallels between General Draude’s ‘radical plan’ and former UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s mandatory service programme, which was marketed toward the end of his Premiership. Like Draude, Sunak believed that mandatory service could help to strengthen the values of mutual respect and social responsibility, which arguably are diminishing in modern society.

General Draude also believes that the ‘radical plan’ could be used as a tool to combat the overbearing ‘college culture’ of the U.S. and U.K.

‘We’re so eager to push our youngsters into college without asking them what they want. I think a lot of it is parents looking for cocktail chatter. “Where’s your kid going to college?”

‘We have to be sensitive to what will make our children happy, not necessarily successful. I know a lot of successful people who are not happy.

‘[The plan] gives you two years to work out what the hell it is you want to do with your life.’

Life After the Marines

General Draude retired from the U.S. Marines in 1993 as a Brigadier General, after thirty years of service for his country. He then enjoyed a successful career in business and insurance working for the United Services Automobile Association, as their head of the U.S. Southeast Region. He retired from USAA in 2003 and went on to be President and Chief Executive Officer of the Marine Corps University Foundation, from 2004 until his retirement in 2015. He now teaches at the University of South Florida.

The next part of this article will explore General Draude’s views on significant political events since his retirement from the Marines. We will be focussing on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the U.S.’s arguably waning role as ‘World Police’ and the intensifying tensions between America and China.

Finally, we will conclude with 3 parting messages from General Draude – for the youth, government and military of America today.

Q: What was your initial reaction to the Authorisation for the Use of Military Force after 9/11?

‘Necessary. It was one of those things we had to do. We needed authorisation to get into the fight.

‘What has been our problem, is we try at times to reach too far. We have a splendid military that can get a lot of things done, but sometimes that becomes a convenient tool to do other things. Because there is the structure, the hierarchy, the money.

‘Let’s have the military not only defeat the enemy, they’ll help us establish a Jeffersonian Democracy in Afghanistan. What?!

‘Strategic narcissism, it’s been a real problem. We don’t know when to say it’s over.’

Q: What were your thoughts leading up to the Iraq War and how do they compare to today?

‘I was all for the Iraq War.

‘I remember seeing General Colin Powell at the UN with the CIA right behind him. He was a great guy; he was well liked.

‘He made a case that I believed on the 17th of March 2003. Yeah this makes sense.

‘What the hell were we thinking? Wasn’t one war enough?’

Q: Were you aware of how the information was received?

‘I didn’t know the source of it.

‘I felt uneasy about terms like “slam dunk” that were given by the CIA. A little too cavalier of a term for something so serious.

‘When it came out…I felt lied to again.’

‘A tremendous deception operation. We’re going to get one of our high-ranking guys, he’s going to be captured, maybe tortured, and he’s then going to give the story that the people not only want to believe, but believe already.’

‘We should have been smarter.

‘And the whole time the body bags just kept coming home.’

Q: What was the Iraq War about in your eyes?

‘It was on the mistaken assumption that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, had been in cahoots with Osama Bin Laden and therefore was a threat to our existence.

‘And that the Iraqi people would welcome us with open arms. We were waiting for the cheering parades. It was based on these false assumptions which made people feel good.

‘They were groundless, incorrect.

‘You don’t get actionable intelligence from torture. You get what the person thinks you want to hear so you stop torturing them.

‘The effect that it has on the person doing the torturing. It must wear away at their soul.’

Q: What were the biggest mistakes made in Afghanistan and Iraq?

‘First was the assumption that we were going to somehow do more than just eliminate the threat to us which was the main reason for us going in. To then let that mission expand, simply because it could.

‘The other, is hubris. We’re Americans, we can do anything and take it in our stride.

‘The egos of so many of our leaders. To not question things. Beware of the guy who is always giving you good news, because they don’t have the guts to tell you the bad news.

‘We’ve got to be careful. Any leader has to surround himself with people who he can trust to tell him things that he doesn’t want to hear.’

Q: What did you think of the U.S. withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan?

‘Iraq, we shouldn’t have been there in the first place. It was time to go.

‘Afghanistan. What’s interesting is many of the intelligence community said that the Afghanis will fight, but the Ukrainians will not. They had it reversed.

‘General McKenzie kept telling the State Department we have got to keep 2500 in Afghanistan because then NATO will keep another 4 to 5 thousand in. Not to fight, just to keep an eye on things. That would make sense. [But it was] not his decision, [it was] the President’s decision.

‘I’m not sure why we didn’t use Bagram as the [extraction] point. Better defended, more runways. It was a tactical decision, so I don’t want to second guess it. But it seems like Bagram would have made more sense.

‘We knew we were leaving. Why wasn’t it better planned or timed?

‘We’re supposed to be able to do this stuff well. It was truly a disaster. Shame on us.’

‘It seemed as if we had target fixation, we’re getting out, and that’s all that mattered. We saw what resulted, people hanging off aeroplanes.’

Q: Should the way in which the U.S. uses Authorisations for the Use of Military Force be changed?

‘No, I think there has to be a degree of trust for the commander on the scene. He cannot fight with the “mother, may I?” situation. There has to be certain permissions, authorities that are resonant with him.

‘Whatever we call it, it’s a way of getting around a declaration of war. It’s a substitute for that without the harsh words.’

Q: Has the U.S.’s role as ‘World Police’ ended?

‘I think there will always be that feeling that we are the world police, because of the power that we have. Along with that comes reputation.

‘The reputation, when it gets down to it, is that Americans will do the right thing for the right reason.

‘Having that image of the policeman who has not only the baton, but also the bottle of water is a positive one. The challenge is to maintain it.

‘Deterrence is Capability multiplied by Will – We must have both.

‘I want the leaders to have the moral courage to do the right thing. It’s tough these days, it really is.’

Q: What do you think about China’s Belt and Road Initiative? Is it a challenge to world hegemony, or just a quick grab of resources?

‘I think the belt and road initiative was brilliant. Absolutely brilliant! Hook them with a contract they can’t fulfil then it goes to them. Really, really smart.

‘I have read that it is easing off, but it has had an effect there’s no doubt about that.

‘Do they really want to fight us? It’s the thing I have a tough time getting my head around. What is it that they want is the question we have to ask?

‘I think there’s a possibility of continuing on and living relatively peacefully. We have our ups and downs and stealing intelligence and things of that nature. That’s competition, we can live with that.’

‘I wonder how long countries like Russia, North Korea, Iran and China can last with people getting a glimpse of what’s outside them.’

‘Russia has a large security force, I realise that. But still, human nature cannot be set aside. We want what’s best for our families, we want a better life for our children. How can you live in those countries and think that is the case?

‘Sometimes a flash point will come along, and that’s what it takes to get people mobilised. I’m not sure what that will be, I just keep thinking that the human nature of people is to not willingly live under an iron fist.’

Messages for The Youth, Government and Military of America Today

The final section of this feature is the only part of the interview for which the General was given preparation time. Here are the General’s parting words – for the youth, government and military of America today.

Youth

‘My message for the youth is that you’re better than so many people give you credit for. I will not stand for my peers bad mouthing your age group.

‘I tell them about the pandemic, when we had to teach online, distanced, walk in, prove you weren’t infected, wipe down the chairs. Your group took that in stride, the resourcefulness of your age group is magnificent.

‘To the youth, continue doing what you’re doing. Be as good as you can be. Taking care of one another is the main thing. Don’t let anyone make you feel like you are not up to the task, you really are.’

Government

‘I’ve never seen our country as divided as it is right now even in the worst days of Vietnam. Where politicians are held hostage by the fringe elements of the party. This is utterly nonsense. There used to be a degree of respect for one another.

‘I’m wondering what will change it. An alien invasion? I’m not talking from the borders, I’m talking Martians. The United States would at least pull together and say wait a minute, we’ve got bigger problems!

‘To quote Rodney King – “Can we all get along?”

‘Our leaders need to show the way and stop the ad hominem attacks and the diatribes. We’re supposed to be better than that, we are god’s creatures.’

Military

‘Being blessed to serve, in my case in uniform, was almost overwhelming at times because of the pride I had and still have of being a Marine. The selflessness that I saw on the part of so many fine young men and women, who put other things in front of themselves.

‘We have to maintain our standards; we can’t give up on what the Marines and military is about. But we have to be smart about the standards, standards to do what?

‘To look good or be good? A lot of being good is the smarts.

‘We have to be adapting to change, not going back to how things used to be. There’s a tendency to try to fight WW2 again, “the good war.” Well that’s not going to happen again. I’m uncomfortable at times talking about the Gulf War, that will never happen again either.

‘We have to study history. Study cultures, study people. Be willing to accept that we are not as good as we thought we were, but we can be better than we are. We just have to keep working at it, you know.’

Glossary

- The Marine Corps – U.S. military branch specialising in amphibious warfare. Often regarded as the most prestigious branch of the U.S. military due to its rigorous standards and elite training.

- Vietcong – Guerrilla force that sought to defeat the U.S. and South Vietnamese Forces in South Vietnam in order to unify Vietnam under the rule of Communist revolutionary and President of North Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh.

- Hamlet – A small rural village. These were often reinforced by the Vietcong, who used plain clothes combatants to hide amongst the villagers.

- Gulf of Tonkin Incident – Two heavily disputed encounters between U.S. and North Vietnamese ships off the coast of North Vietnam in August 1964. The U.S.’s claim that they were attacked by Vietnamese patrol boats gave way to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which in turn gave President Lyndon B. Johnson authority to use military force in Vietnam – marking the beginning of large-scale U.S. intervention in Vietnam.

- Pensacola Flight School – The primary training facility for U.S. Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard aviators.

- Saddam Hussein – The authoritarian President of Iraq from 1979 until his capture in 2003.

- The U.S. as ‘World Police’ – The long-held belief that the U.S. will act to solve international moral abuses.

© 2024 James Keegan. All rights reserved.

Contact Me

To get in touch, please follow the link below.

Alternatively, connect with me through my LinkedIn which can be found at the bottom of this webpage.